by topics

Topic: Urban sustainability

B

Biodiversity

C

Circular economy

C

Collaborative consumption

C

Command-and-control policy

C

Compact cities

‘Cities of a form and scale appropriate to walking, cycling and efficient public transport, and with a compactness that encourages social interaction’ (Jenks, Burton & Williams, 1996, p.3).

C

Competitiveness

C

Cradle to Cradle

D

Design for Disassembly (DFD)

D

Doughnut economics

E

Ecological democracy

E

Ecological footprint

E

Ecological revitalization

E

Ecology

E

Economic growth

‘Economic growth is an increase in the production of economic goods and services, compared from one period of time to another. It can be measured in nominal or real (adjusted for inflation) terms. Traditionally, aggregate economic growth is measured in terms of gross national product (GNP) or gross domestic product (GDP), although alternative metrics are sometimes used’ (Investopedia, 2019a).

E

Economic space

E

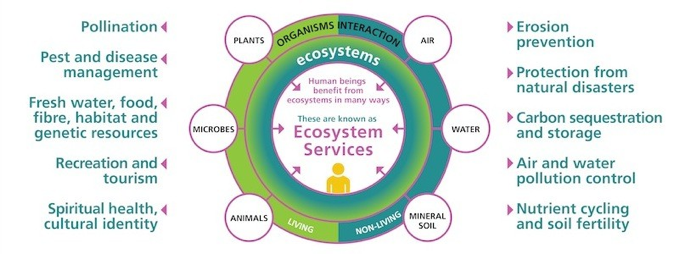

Ecosystem services

G

Gentrification

‘A process of neighbourhood transformation in which working-class and poor residents are displaced by an influx of middle-class residents’ (Hammel, 2009, p.360).

G

Green building

‘Green building is a practice of reducing the environmental impact of buildings and enhancing the health and wellbeing of building occupants by:

- Planning throughout the life-cycle of a building or a community, from master planning and siting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation, and demolition with a focus on the impact to both the environment and people.

- Optimising efficient use of energy, water, and other resources to avoid overconsumption and adopting the use of renewable energy and eco-friendly materials to minimise carbon footprint and emission.

- Reducing the production of waste and preventing pollution of areas like water, air, noise and land.

- Enhancing indoor environmental quality through natural ventilation and lighting as well as good indoor air quality by design and other means.’

(Hong Kong Green Building Council, 2019)

G

Green building assessments

G

Green infrastructure

H

Hybrid design

J

Just city

L

Life-cycle assessment

L

Local/Community economy

L

Low carbon cities

A low carbon city is one that comprises ‘societies that consume sustainable green technology, green practices and emit relatively low carbon or GHG as compared with present day practice to avoid the adverse impacts on climate change’ (Kementerian Tenaga & Teknologi Hijau dan Air (KeTTHA), Malaysian Government, 2011, p.11).

L

Low carbon urbanism

M

Market-based / Economic-incentive

N

New towns

‘New Towns are cities or towns that are designed from scratch and built in a short period of time. They are designed by professionals according to a Master Plan on a site where there was no city before. This distinguishes a New Town from a ‘normal’ city that gradually grows and evolves over time. Also, New Towns are mostly the result of a political (top-down) decision. The building of a new city ‘from scratch’ is a heroic enterprise that challenges the architect or planner to find the ideal shape for the urban program according to the state of the art planning ideas. A New Town is always a reflection of one moment in time and the ambitions of that moment’ (International New Town Institute, 2019).

‘Hong Kong has developed nine new towns since the initiation of its New Town Development Programme in 1973. The target at the commencement of the New Town Development Programme was to provide housing for about 1.8 million people in the first three new towns, namely, Tsuen Wan, Sha Tin and Tuen Mun. (...) The first (Tsuen Wan, Sha Tin and Tuen Mun) started works in the early 1970s; then the second (Tai Po, Fanling/Sheung Shui and Yuen Long) in the late 1970s; and the third (Tseung Kwan O, Tin Shui Wai and Tung Chung) in the 1980s and 1990s. (...) All the new towns accommodate public and private housing supported by essential infrastructure and community facilities. External transport links were developed with all new towns now served by rail links to the urban area and road links to the adjacent districts. Further enhancement of road links is ongoing’ (Hong Kong: The Facts, 2016).

P

Passive design

P

Politics

P

Poverty

Poverty ‘encompasses living conditions, an inability to meet basic needs because food, clean drinking water, proper sanitation, education, health care and other social services are inaccessible’ (Compassion International, n.d.).

P

Public space

‘Property that is open to public use, including streets, sidewalks, parks, plazas, malls, cafes, interior courtyards, and so forth. It can be privately or publicly owned’ (Mitchell & Staeheli, 2009, p.511).

R

Redevelopment

A business strategy that involves ‘replacing old dilapidated buildings with modern, quality and environmentally-friendly schemes, enhancing the quality of the living environment through restructuring and re-planning of older districts’ and ‘providing appropriate community facilities and open space’ (Urban Renewal Authority, 2012).

R

Right to the city

S

Social justice

S

Social polarization

‘Social polarization is the process of segregation within a society that may emerge from income inequality, economic restructuring, etc. and result in such differentiation that would consist of various social groups, from high-income to low-income. It is the process of growth of low-skilled service jobs at the same time of the expansion of elite of higher professionals’ (Surt Foundation, 2010).

S

Social reform

One of the four planning traditions, in which ‘[t]he tradition of social reform focuses on the role of the state in societal guidance. It is chiefly concerned with finding ways to institutionalize planning practice and make action by the state more effective; Under this mindset, planners work for a ‘“scientific endeavor”, and one of their main preoccupations is with using the scientific paradigm to inform and to limit politics to what are deemed to be its proper concerns’ (Friedmann, 1988, pp.11-12). While striving for change, the plan actually reinforces the existing power relationship.

S

Socio-spatial segregation

S

Spatial justice

‘Spatial Justice is a term put forward by the critical urbanist Ed Soja in his book Seeking Spatial Justice. It calls for a reflection on urban space focused on the spatial nature of social interaction and the inequalities that are produced and reproduced through spatial relationships. In a way, seeking spatial Justice advocates for greater control over how spaces are produced. In the words of Ed Soja spatial justice “seeks to promote more progressive and participatory forms of democratic politics and social activism, and to provide new ideas about how to mobilise and maintain cohesive collations and regional confederations of grassroots social activist.” In a way, seeking spatial Justice is about people’s control over how urban space is imagined, planned/designed and lived. It is both a goal and a tool to be used in the process of design’ (100 Resilient Cities, 2004).

S

Sponge city

S

Sustainable cities

‘The city that while providing a high quality of life to a diversified and plural society in the present, establishes the mechanisms necessary to ensure suitable economic and social growth in the long term while maintaining the natural resources of the environment. This will allow future generations of citizens to satisfy their needs on the same terms’ ( Garca-Sãnchez & Prado-Lorenzo, 2010, p.2746).

S

Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)

‘The Sustainable Development Goals are the blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. They address the global challenges we face, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation, prosperity, and peace and justice. The Goals interconnect and in order to leave no one behind, it is important that we achieve each Goal and target by 2030.’ (United Nations, n.d.)

T

Town Planning Ordinance

The Town Planning Ordinance is a procedural legal document and legislation ‘to promote the health, safety, convenience and general welfare of the community by making provision for the systematic preparation and approval of plans for the lay-out of areas of Hong Kong as well as for the types of building suitable for erection therein and for the preparation and approval of plans for areas within which permission is required for development’ (Department of Justice, 2017).

U

Unplugged design

U

Urban development

U

Urban ecology

U

Urban hydrology

U

Urban metabolism

U

Urban resilience

U

Urban stormwater runoff

W

World City Ranking

Reference List

100 Resilient Cities. (2004). Teaching Spatial Justice. Retrieved from https://www.100resilientcities.org/teaching-spatial-justice/

100 Resilient Cities. (n.d.). What is Urban Resilience? Retrieved from http://www.100resilientcities.org/resources/

American Museum of National History. (n.d.). ‘What is Biodiversity?’. Retrieved from https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/about-the-cbc/what-is-biodiversity

Baldwin, C., & King, R. (2018). Social sustainability, climate resilience and community-based urban development: What about the people? New York: Routledge

British Ecological Society. (n.d.). ‘What is ecology?’. Retrieved from https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/about/what-is-ecology/

Brown, G., McLean, I., & McMillan, A. (2018). Politics. A Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics and International Relations (4th ed.). Oxford University Press, 62. Retrieved from https://www-oxfordreference-com.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/view/10.1093/acref/9780199670840.001.0001/acref-9780199670840-e-1042?rskey=8ogTnr&result=1229

Caner, Gizem & Bölen, Fulin. (2013). Implications of Socio-spatial Segregation in Urban Theories. Planlama 2013; 23(3): 153-161. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e427/bc2e98244f70db675ac11b370db3b9d5000a.pdf

Compassion International. (n.d.). ‘What is Poverty?’. Retrieved from https://www.compassion.com/poverty/what-is-poverty.htm

Department of Justice (2017). Town Planning Ordinance. Retrieved from https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap131?xpid=ID_1438402658985_001.

Derudder, B. (2009). World/Global Cities. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, p.262-268.

Drainage Service Department, Hong Kong Government. (2017). Sponge City: Adapting to Climate Change. Sustainable Report 2016-17. Retrieved from https://www.dsd.gov.hk/Documents/SustainabilityReports/1617/en/sponge_city.html

El-Zeind, Charles. (2012). Defining Local Economies: Implications For Community Development And Social Capital. Sustainable Business Toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.sustainablebusinesstoolkit.com/local-economies-community-development-social-capital/

Endlicher, W., Langner, M., Hesse, M., Mieg, H.A., Kowarik, I., Hostert, P., Kulke, E., Nutzmann, G., Schulz, M., Meer, E., Wessolek, G. & Wiegand, C. (2007). Urban Ecology – Definitions and Concepts. Shrinking Cities: Effects on Urban Ecology and Challenges for Urban Development.

Environmental Protection Agency, the United States. (2009). Executive Summary. Ecological Revitalization: Turning Contaminated Properties into Community Assets. ES-1-ES-2. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-04/documents/ecological_revitalization_turning_contaminated_properties_into_community_assets.pdf

Fainstein, S.S. (2005). Cities and Diversity: Should We Want It? Can We Plan for It? Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 41(1), pp.3-19.

Friedmann, J. (1988). Reviewing Two Centuries. Society, 26(1), pp.7-15.

Friedmann, J. (2002). Life Space and Economic Space: Third World Planning in Perspective [Book cover]. Transaction Publishers, USA.

Garca-Sãnchez, Isabel-Marãa & Prado-Lorenzo, , Josã-Manuel. (2010).

Grover, V. (2011). Cradle-to-Cradle. In Green Business: An A-to-Z Guide. 122-124. Retrieved from http://sk.sagepub.com.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/reference/greenbusiness/n35.xml

Hagerman, C. (2011). Green Infrastructure. 223-229. Retrieved from http://sk.sagepub.com.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/reference/greencities/n70.xml

Hammel, D.J. (2009). Gentrification. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, p.360-367.

Harvey, D. (2008). The Right to The City. New Left Review 53, p.23-40.

Holden, E. (2012). Ecological Footprint. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, 6-11. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-047163-1.00581-6

Hong Kong Green Building Council. (2019). What is Green Building. Retrieved from https://www.hkgbc.org.hk/eng/greenbuilding.aspx

Hybrid Space Lab. (n.d.). Hybrid Design. Retrieved from http://hybridspacelab.net/hybrid-design/

International New Town Institute. (2019). What is a new town? Retrieved from http://www.newtowninstitute.org/spip.php?article415

Investopedia. (2019a). Economic Growth. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/economicgrowth.asp

Jenks, M., Burton, E., & Williams, K. (1996). ‘Introduction: Sustainable Urban Form in Developing Countries?’. In The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? London: E & FN Spon, 1-6

Kementerian Tenaga & Teknologi Hijau dan Air (KeTTHA), Malaysian Government. (2011). Low Carbon Cities Defined. Low Carbon Cities – Framework and Assessment System. 11-13. Retrieved from http://lccftrack.greentownship.my/files/LCCF-Book.pdf

Kupriyanov, V.V. 2009. Urban hydrology. In: The Hydrological Cycle, Volume III, The Encyclopedia of Life

Support Systems, I.A. Shiklomanov (Ed.). pp. 141-160.

Lewis, N. (2009). Competitiveness. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, p.226-233.

Li, Susie (2015). ‘DfD Buildings: What is Design for Disassembly?’. Poplar. Retrieved from https://www.poplarnetwork.com/news/dfd-buildings-what-design-disassembly

Li, Y., Chen, X., Wang, X., Xu, Y., & Chen, P. H. (2017). A review of studies on green building assessment methods by comparative analysis. Energy and Buildings, 146, 152-159. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778817314858

McGee, Caitlin. (2013). Passive design. Your Home, Australian Government. p.87-89 Retrieved from http://www.yourhome.gov.au/sites/prod.yourhome.gov.au/files/pdf/YOURHOME-PassiveDesign.pdf

Mitchell, D. & Staeheli, L. A. (2009). Public space. International Encyclopaedia of Human Geography, p.511-516.

Mitchell, R. (2006). Green politics or environmental blues? Analyzing ecological democracy. Public Understanding of Science, 15(4), 459-480. Retrieved from http://lib.icimod.org/record/12332/files/732.pdf

New Towns, New Development Areas and Urban Developments (2016). Hong Kong: The Facts. New Towns, New Development Areas and Urban Developments. Retrieved from https://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/factsheets/docs/towns&urban_developments.pdf

Newman, K. (2009). Social Justice, Urban. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, pp.195-198.

OECD. (2001). Command-and-control Policy. Glossary of Statistical Terms. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=383

OECD. (2007). Market-based Instruments. Glossary of Statistical Terms. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=7214

Perren, Rebeca & Grauerholz, Liz. (2015). Collaborative Consumption. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 139-144.

Poole, K., & Shuman, M. (2014). Local Economy. In D. Rowe (Ed.), Achieving Sustainability: Visions, Principles, and Practices (Vol. 2, pp. 513-519). Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA. Retrieved from https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3709800091/GVRL?u=cuhk&sid=GVRL&xid=71d4d76a

Raworth, Kate. (2017). ‘What on Earth is the Doughnut?’. Kate Raworth – Exploring doughnut economics [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/

Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems, CGIAR. (2014). ‘What are ecosystem services?’. Ecosystem services and resilience framework. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). Retrieved from https://wle.cgiar.org/content/what-are-ecosystem-services

Rodgers, S. (2009). Urban Growth Machine. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, p.40-45.

Sharpe, S., & Giurco, D. (2018). From trash to treasure: Australia in a take–make–remake world. Australian Quarterly, 89(1), 19-44. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26450192

Stewart, Alicia & Radspinner, Krista. (n.d.). The Unplugged Office Space and the Role of Sustainable Design in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://uncw.edu/csurf/documents/stewartradspinner_000.pdf

Surt Foundation. (2010). Key term definition: Social polarisation. Retrieved from https://understandingsocialscience.wordpress.com/2010/01/08/key-term-definition-social-polarisation/

‘Sustainable Cities’ in Warf, B. (2010) Encyclopedia of Geography (Vol.6), Sage Publications, pp.2746-2747.

The Global Development Research Centre. (n.d.). Life Cycle Analysis. SD Features – Sustainability Concepts. Retrieved from http://www.gdrc.org/sustdev/concepts/17-lca.html

The United Nations (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Theodorson, G. (1969). A modern dictionary of sociology. New York: Crowell.

Thormark, Catarina. (n.d.). Motives for design for disassembly in building construction. Retrived from https://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB11732.pdf

Trischler, H. (2013). Introduction. RCC Perspectives, (3), 5-8. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26240505

Urban Renewal Authority, Hong Kong Government. (2012). A Mission of 4 Rs. Retrieved from https://www.ura.org.hk/f/publication/2012/ch04-a_mission_with_4rs.pdf

Urban Waste. (n.d.). Urban Metabolism. Retrieved from http://www.urban-waste.eu/urban-metabolism/

Utah State University Extension. (2017). Urban Stormwater. Retrieved from http://extension.usu.edu/waterquality/urbanstormwater/